History informs us that some people, especially the wealthy, flee cities in response to pandemics and other major catastrophes.1 Media accounts and preliminary empirical research suggest the response to the COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. Nearly half a million people reportedly fled hard-hit New York City within two months of the World Health Organization declaring the coronavirus disease a global pandemic.2 Many of those leaving the state were residents of some of New York City’s wealthiest neighborhoods,4-6 while others were renters who lost their jobs in the economic shutdown.3

Studies of earlier crises suggest this exodus from New York City may be temporary. In past pandemics and crises, refugees have typically returned, remaining attracted to the social and cultural dynamism cities like New York offer.7 This was certainly the case following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, when a strong sense of patriotism supplanted fears of subsequent attacks.8 However, the circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic raise questions about the future attractiveness of large cities as places to live and do business.

It’s important to note a major exodus of both people and jobs was underway prior to the pandemic. Corporations were relocating headquarters and transferring jobs from large cities to smaller, more affordable cities – often in the South.9-10 New York City residents followed — and, in some instances, led — the departure of businesses and jobs, at an average rate of 227 per day in 2018.9,11

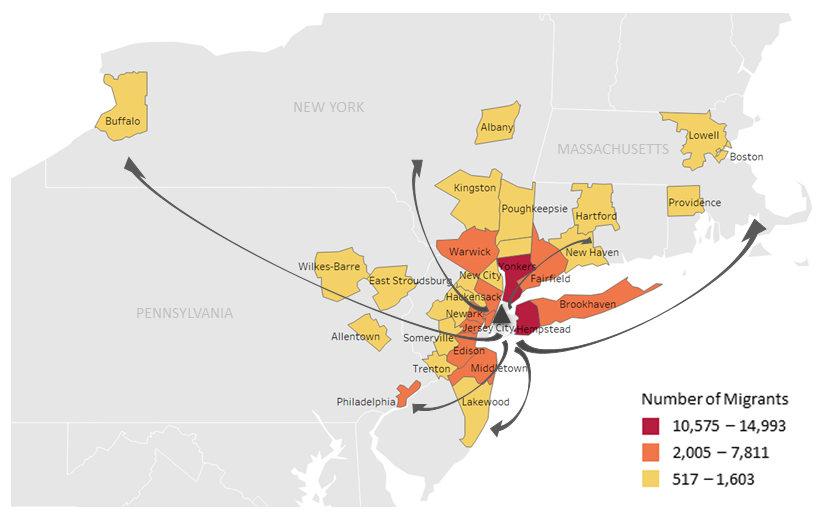

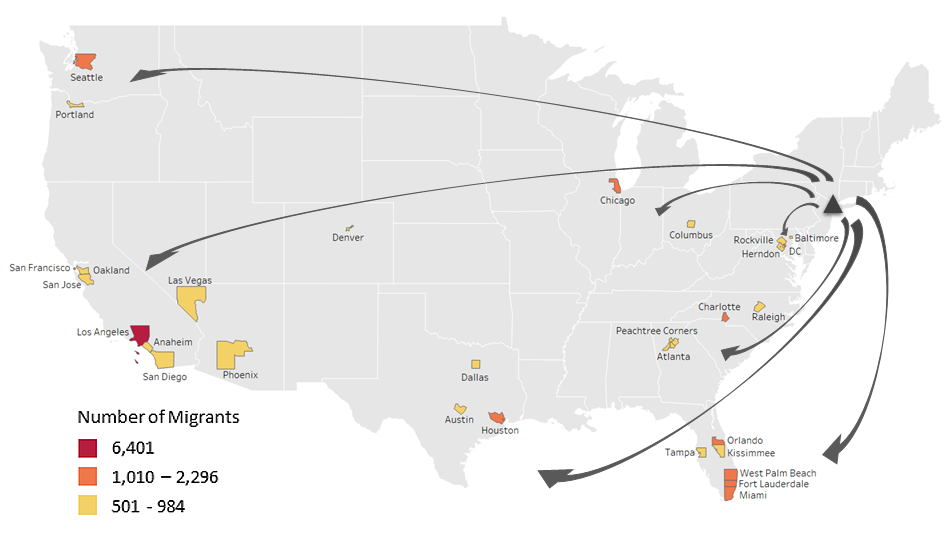

Many of those who left moved to nearby suburbs and other more affordable communities in the Northeast (Figure 1). Others made long-distance moves to small, medium and large cities and towns in other regions of the country (see Figure 2). 9,12-13

Prior to the pandemic, large U.S. cities – especially immigrant gateways – were already beginning to experience a slowdown in the influx of international migrants due to the Trump Administration’s anti-immigration rhetoric and policymaking.14-19 The situation worsened during the pandemic, with travelers from a host of countries banned, and restrictions imposed on just about everyone seeking entry into the U.S., including temporary workers (agricultural and high tech), family members of legal permanent residents, asylum seekers and international students.

The economic impact of these policies on the tax base of large U.S. cities could be devastating. It is conceivable that both international tourists and aspiring migrants offended by the Trump Administration’s scapegoating of immigrants in the pandemic might choose cities in other countries as places to visit, study and take up future residence.20

It is difficult to predict future migration behavior given the evolving spatio-temporal pattern of coronavirus infections and deaths. Some New York City coronavirus refugees fled to destinations perceived to be safe havens from the pandemic that subsequently turned out to be hotspots for community spread of the virus.21 Given that the flashpoint of the pandemic shifted from the Northeast to the South — the nation’s most rapidly growing region for the past several decades22 — this raises serious questions about future regional population shifts. Will Florida, North Carolina, and other Southern magnet states remain highly desirable destinations for migrants?

Some urban experts forecast a major move away from dense urban living and a renewed preference for suburban and exurban living, where it is easier to practice social distancing. For example, Kotkin asserts that “…dense cities particularly have a lot going against them … People will continue to move more into the periphery and into smaller cities, where basically you can get around without getting on (public) transit.”23

Citing a Harris Poll, Menton reports, “… nearly a third of Americans are considering moving to less densely populated areas in the wake of the pandemic.” She goes on to note that “[p]eople want to stay away from public elevators and sharing of common laundry areas … People are expressing concern about living in high rises with common amenities.”

And while only time will tell if these and other prognoses of a continued — and perhaps accelerated — urban exodus will fully materialize, the extent to which remote work will become the new norm in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic also will likely influence future migration and residential settlement patterns. Several major corporations, including Twitter, Facebook and Spotify, have already decided to allow certain segments of their workforce to work remotely on a permanent basis.24 Other corporations, as well as some government and nonprofit organizations, may do the same. Such decisions will have enormous implications for whether pandemic refugees will return to expensive urban markets or seek out less dense suburban, exurban and rural destinations in the South and other regions of the country.

A recent survey of 4,000 employees in major tech companies found that 69 percent of New Yorkers in the tech and finance fields would consider relocating if they knew they could work from home permanently. Eighteen percent would leave the metro area, 36 percent would move out of state and 15 percent would leave the country.25-27 The shift to virtual work has led one group to forecast that 25-30 percent of the U.S. workforce will work from home multiple days a week by the end of 2021, up from 3.6 percent prior to the pandemic.28

Reflecting on the implications, one writer said, “That means employees may not need to live in the city where their company is headquartered.” Another posed the question: Is this the end of the tech hub?29 Does it also mean the demand for coworking spaces in cities will decline sharply or perhaps end?29-30

An increasing number of communities with slow-growing or declining populations are offering migration incentives to encourage remote workers and others to leave high-cost urban centers and relocate to their communities.31-38 The incentives, which include relocation expenses, tax credits, forgivable mortgages, student loan repayment, cash and land, could potentially influence workers’ decisions of whether and where to move in future.

Finally, a critical question: Will the way states and cities respond to the Black Lives Matter protest movement influence future migration trends? The movement has extended to nearly every city in America, with violent confrontations in some instances, while at the same time the country is battling a pandemic. The impact of these twin crises on the human psyche and future migration intentions remains unknown and difficult to predict.

1 Edelstein, M., Koser, K., & Heymann, D. (2014). Health Crises and Migration. Forced Migration Review, Crisis, 97-112. doi:10.4324/9780203797860-5

2 Sound Health and Lasting Wealth. (2020, May 24). Young people are joining the rich in leaving NYC for cheaper, less dense cities after coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.soundhealthandlastingwealth.com/covid-19/young-people-are-joining-the-rich-in-leaving-nyc-for-cheaper-less-dense-cities-after-coronavirus/

3 Hall, M. (2020, April 06). Could The Coronavirus Be A ‘Turning Point’ For New Yorkers To Leave En Masse? Bisnow. Retrieved from https://www.bisnow.com/new-york/news/economy/population-loss-coronavirus-migration-103754

4 Quealy, K. (2020, May 15). The Richest Neighborhoods Emptied Out Most as Coronavirus Hit New York City. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/15/upshot/who-left-new-york-coronavirus.html?action=click

5 Helmore, E. (2020, March 13). Coronavirus lifestyles of the rich and famous: How the 1% are coping. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/13/coronavirus-lifestyles-of-the-rich-and-famous-how-the-1-are-coping

6 Cuccinello, H. C. (2020, June 26). Billionaire Tracker: Actions The World’s Wealthiest Are Taking In Response To The Coronavirus Pandemic. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/hayleycuccinello/2020/03/17/billionaire-tracker-covid-19/

7 Davidson, J. (2020, April 13). The Return of Fear in New York. New York Magazine. Retrieved from https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/04/return-of-fear-nyc-coronavirus.html

8 Cuccinello, H. C. (2020, June 26). Billionaire Tracker: Actions The World’s Wealthiest Are Taking In Response To The Coronavirus Pandemic. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/hayleycuccinello/2020/03/17/billionaire-tracker-covid-19/

9 Hill, C. (2019, December 19). 3 Reasons So Many People are Getting the Hell Out of the Northeast. MarketWatch. Retrieved from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/3-reasons-so-many-people-are-getting-the-hell-out-of-the-northeast-2018-10-20

10 Cowen, T. (2020, March 31). What Will Post-pandemic New York City Look Like? Marginal Revolution. Retrieved from https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2020/03/what-will-post-pandemic-new-york-city-look-like.html

11 Lee, A. (2019, May 03). Here’s Why Millennials Are Leaving New York (and Where They’re Headed Instead). Apartment Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/new-yorkers-move-to-la-258453

12 Kelly, J. (2019, September 06). New Yorkers Are Leaving The City In Droves: Here’s Why They’re Moving And Where They’re Going. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2019/09/05/new-yorkers-are-leaving-the-city-in-droves-heres-why-theyre-moving-and-where-theyre-going/

13 Lu, W., & Tanzi, A. (2019, August 29). How Many People Live in New York City? More Leave Every Day. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-29/new-york-city-metro-area-exodus-soars-to-277-people-every-day

14 Chishti, M., & Pierce, S. (2020, July 16). Crisis within a Crisis: Immigration in the United States in a Time of COVID-19. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/crisis-within-crisis-immigration-time-covid-19

15 Forrester, A. C, & Nowrasteh, A. (2020, April 21). No, Mr. President, Immigration Is Not Correlated with COVID-19 in the United States. Cato Institute. Retrieved from https://www.cato.org/blog/no-mr-president-immigration-not-correlated-covid-19-united-states

16 Somin, I. (2020, June 29). The Danger of America’s Coronavirus Immigration Bans. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/danger-americas-coronavirus-immigration-bans/613537/

17 Darbhamulla, S. (2020, July 29). Trump’s COVID-19 Visa Ban May Alter the Face of American Immigration Beyond the Pandemic. The Chicago Reporter. Retrieved from https://www.chicagoreporter.com/trumps-covid-19-visa-bans-may-alter-the-face-of-american-immigration-beyond-the-pandemic/

18 NAFSA. (2020, August 18). COVID-19 Restrictions on U.S. Visas and Entry. Retrieved from https://www.nafsa.org/regulatory-information/covid-19-restrictions-us-visas-and-entry

19 Migration Policy Institute. (2020, July 01). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resources. Retrieved from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/topics/coronavirus

20 Mcgeehan, P. (2020, July 24). Broadway Is Dark. Liberty Island Is Empty. Will the Tourists Come Back? The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/24/nyregion/nyc-tourism-coronavirus.html

21 Mervosh, S., & Tavernise, S. (2020, April 19). America’s Biggest Cities Were Already Losing Their Allure. What Happens Next? The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/19/us/coronavirus-moving-city-future.html

22 Johnson, J. H., Jr., & Parnell, A. M. (2019, July 09). Seismic Shifts. Business Officer Magazine. Retrieved from https://businessofficermagazine.org/features/seismic-shifts/

23 Jones, A., & Shoichet, C. E. (2020, May 02). Coronavirus is Making Some People Rethink Where They Want to Live. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/02/us/cities-population-coronavirus/index.html

24 Menton, J. (2020, May 01). Get Me Out of Here! Americans Flee Crowded Cities Amid COVID-19, Consider Permanent Moves. USA Today. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2020/05/01/coronavirus-americans-flee-cities-suburbs/3045025001/

25 Ruiz, K. (2020, May 23). Young people are joining the rich in leaving NYC for cheaper, less dense cities after coronavirus. Daily Mail. Retrieved from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8345919/Young-people-joining-rich-leaving-NYC-cheaper-dense-cities-coronavirus.html

26 Zillow. (202, May 13). A Rise in Remote Work Could Lead to a New Suburban Boom. Retrieved from http://zillow.mediaroom.com/2020-05-13-A-Rise-in-Remote-Work-Could-Lead-to-a-New-Suburban-Boom

27 Crum, R. (2020, March 24). Coronavirus: Glassdoor survey finds people confident about long-term working from home. The Mercury News. Retrieved from https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/03/23/coronavirus-glassdoor-survey-finds-people-confident-about-long-term-working-from-home/

28 Lister, K. (2020, April 12). Work-at-Home After Covid-19-Our Forecast. Global Workplace Analytics. Retrieved from https://globalworkplaceanalytics.com/work-at-home-after-covid-19-our-forecast

29 Roepe, L. (2020, April 04). Will COVID-19 be the death of coworking spaces? Marketplace. Retrieved from https://www.marketplace.org/2020/04/03/will-covid-19-be-the-death-of-coworking-spaces/

30 Baskerville, G., Clarke, K., & Novogradac, M. (2020, June 11). Opportunity Zones Market Trends And Covid-19. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/sorensonimpact/2020/04/30/opportunity-zones-market-trends-and-covid-19/

31 Adamczyk, A. (2019, August 31). 6 US cities and States that will Pay You to Move There. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2019/08/31/6-us-cities-and-states-that-will-pay-you-to-move-there.html

32 Pesce, N. L. (2019, December 17). These 13 Cities, States, and Countries Will Pay You to Move There. MarketWatch. Retrieved from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/these-9-cities-states-and-countries-will-pay-you-to-move-there-2018-10-26

33 Glassdoor. (2019, June 17). Cities & States That Will Pay You to Move There: Glassdoor. Retrieved from https://www.glassdoor.com/blog/cities-states-that-will-pay-you-to-move-there/

34 The Penny Hoarder. (2019, October 02). Ready for a Change of Scenery? These 9 Cities Will Pay You to Move There. Retrieved from https://www.thepennyhoarder.com/make-money/places-that-will-pay-you-to-move-there/

35 Shrikant, A. (2020, June 22). 11 Places Around the World That Will Pay You to Move or Live There. Acorns. Retrieved from https://grow.acorns.com/places-around-the-world-that-will-pay-you-to-move-there/

36 Garfield, L., & Brandt, L. (2020, February 04). 11 places in the US that are offering new residents big incentives to move there. The Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/us-cities-pay-people-move-incentives-2018-7

37 Ocampo, S. (2020, March 04). These Cities Will Pay You to Move There in 2020. MoveBuddha. Retrieved from https://www.movebuddha.com/blog/get-paid-to-move/

38 Hoagland, M. (2020, July 27). Commentary: Millennials, Restart Your Life in a Small Town. DailyYonder. Retrieved from https://dailyyonder.com/commentary-millennials-restart-your-life-in-a-small-town/2020/07/28/

39 Zaveri, M. (2020, July 27). The Uncertain Future of Midtown. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/27/nyregion/nyc-midtown-manhattan-coronavirus.html?searchResultPosition=1

40 Ewing, R., & Hamidi, S. (2015). Compactness versus Sprawl: A Review of Recent Evidence from the United States. Journal of Planning Literature, 30(4), 413-432. doi:10.1177/0885412215595439